By Kemuel Othieno

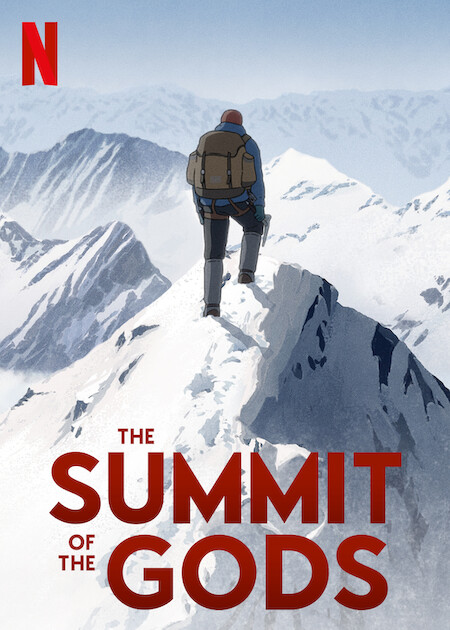

Le Sommet Des Dieux is in every way a credit to animation. It was based on the gekiga (Japanese comic), Kamigami no Itadaki, which was written by Jiro Taniguchi between 2000 and 2003. It is available for streaming on Netflix under its English title, Summit of the Gods. The film was directed by Patrick Imbert and released in 2021 to wide acclaim, winning the César Award for Best Animated Film the year after its release.

The story follows Japanese photographer Makoto Fukamachi who believes he has discovered the camera of a famous mountaineer believed to have died on Everest. The camera is intercepted and stolen by a young mountaineer named Habu Joji. Habu Joji has also been missing since a trip to Everest went wrong. Fukamachi returns to Japan but is obsessed with the camera and Habu’s story. He interviews a few people who knew Habu before deciding to try and track him down in Kathmandu. After a bit of convincing, Habu agrees to let Makoto document his attempted ascent of the southwestern face of Everest in the dead of the winter.

The movie is in every way a triumph of storytelling. Imbert succeeds in capturing the magic in mountaineering that has led thousands to throw their lives at the mercy of nature. Imbert’s adaptation shows admiration for nature before anything else, recognising the raw power of it all. It shows admiration for the sport of mountaineering and does not create a spectacle out of what is already majestic, instead letting the beauty speak for itself.

In an interview with Paris Match, Patrick Imbert addressed the specifics of the film’s age rating. “What’s funny is that for a long time, the producers insisted to investors that it was a family film. Which implies that parents can bring their children to see the film. However, it is obvious that it is not at all for children, at least not before the age of twelve I think,” he said. It is clear that Le Sommet Des Dieux benefitted from a more grounded approach, abandoning the whimsy that many associate with animation for a more realistic take. It is not surprising though considering that Jiro Taniguchi’s work as an artist was geared towards adults as is always the case with gekiga.