By Enock Wanderema

In an article posted on the WHO website in 2018, porcine tapeworm (T. solium) imposes a serious public health, agricultural, and economic threat, yet – mostly in pork-consuming developing countries – the infection caused by this zoonotic tapeworm in humans has been neglected.

The Indian Journal of Medical Research provides that this infection is the most common single cause of seizures/epilepsy in India and several other endemic countries throughout the world, doubling as the most common parasitic disease of the brain caused by the pork tapeworm.

To the pork-eating community, “It is the sweetest,” says Samuel Tatambuka, Uganda Christian University (UCU) Communication Assistant. He adds that pork is soft and has a nice texture while chewing it. Tatambuka jokes that it should have been on the Ugandan Court of Arms. This could explain why it takes up a consumer percentage of 34 on the global meat production scale.

According to the Daily Monitor, 3.5kg is consumed per Ugandan head annually. putting the country first in East Africa for pork consumption On the African scene, a 2022 report showed Angola leading with 6.1kg per head.

However, pork consumption is not the problem; blame it on the pig’s problematic digestive system. According to Dr. Axe, a pig digests whatever it eats rather quickly, up to about four hours. On the other hand, a cow takes a good 24 hours to digest what it’s eaten.

It is through the digestive process that most of the food-borne parasites and toxins are taken out of the system. Given the basic digestion process of a pig, consumed parasites are presumed to be intact, hence furthering their active role.

According to Elly Odule Ekajang, a UCU mass communication student with experience in pig farming, pigs have poor immunity. “It is advisable to immunize pigs every three weeks because they take in almost every bit of dirt that ever existed,” notes Odule.

“With that in consideration, we feed our pigs at the farm on recommended foods to ensure their health,” adds Odule.

On that note, studies have shown that when a pig that has eaten from contaminated fields and harbored the tapeworm is slaughtered, the meat itself is most likely to shelter the parasite, and if improperly cooked, the pork eating community will take in the pork tapeworm.

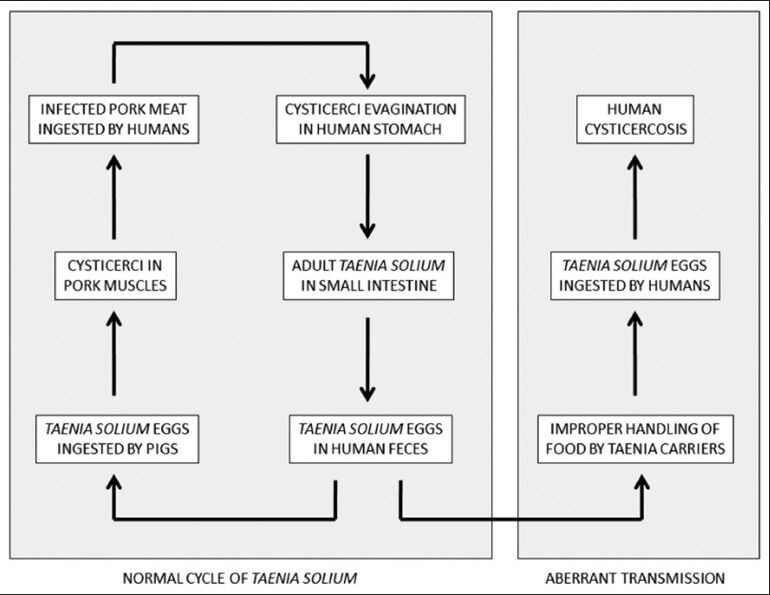

In the process of spreading inside the human body, a mature porcine tapeworm will lay eggs. At the larval stage, the parasite will infect the nervous system, hence causing neurocysticercosis (NCC), a severe variation of the tissue infection – thus ranking high on the Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) charts as the main zoonotic foodborne pathogen in the world.

Approximately 50 million people worldwide have neurocysticercosis, and it is the leading cause of acquired epilepsy in many endemic countries.

On that note, a person infected with the pork tapeworm can poorly excrete its eggs through feces, which will be taken in by the pigs that are mostly on a free-range rearing system, hence recycling the process.

This also explains that if there is less effort to improve sanitation and the pig rearing system, the pork tapeworm infection will be maintained.

One would argue that there are fewer clinical facts backing up the regulation of pork consumption. This is, on one hand, true, but also acquired studies confirm that about 30% of epileptic cases are caused by the pork worm parasite.

Ten out of ten interviews made with average pork consumers at UCU have given off that most people only associate epilepsy with being hereditary. “I did not know it could lead to acquired epilepsy, maybe obesity, if over consumed,” says Rachel Mirembe Sserwadda, UCU’s guild president.

Nakayenze Priscilla, a UCU former student, notes that she never eats roasted pork. “It is never ready,” she says. She adds that after buying raw pork, she washes it thoroughly, and then boils it for an average of an hour. Here, she will do whatever spicing that favors the occasion.

If pork has to take a length of time while cooking just to get rid of parasites, then this leaves us with other risk factors such as poor sanitation, under which are lack of latrines, unclean drinking water, poor pig husbandry, inadequate meat inspection, and lack of knowledge about the causative tapeworm.

The pork consuming community can check these risk factors for them to enjoy their “skin rejuvenating meat,” as Tatambuka calls it.