By Agatha N Biira

In Uganda, December is a magical time of the year. For weeks leading up to Christmas, markets are filled with people buying food and decorations, while shops and boutiques are packed with people looking for the perfect outfit for the big day.

The traffic jam in Kampala, the country’s capital, is even more pronounced during this time as people make last-minute preparations and others travel upcountry to spend the holidays with their loved ones. And as the year ends, people make plans and resolutions for the new year. But as anyone would anticipate, that wasn’t the case for 2020.

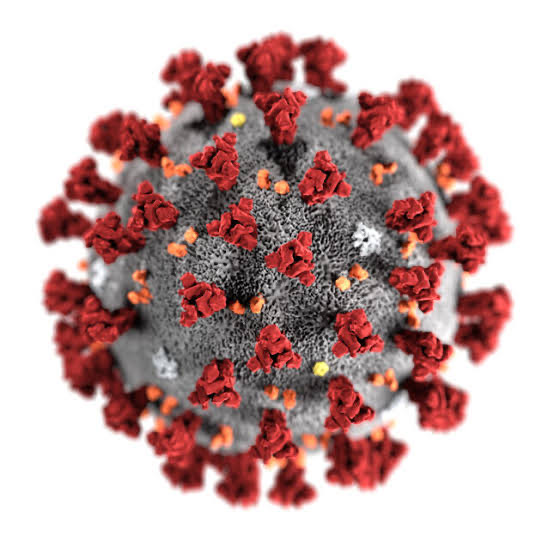

Seven days into the New Year, Chinese officials announced that they had identified a highly infectious virus, SARS-CoV-2 (coronavirus), that causes respiratory illness in people. Four days later, they announced their first death in Wuhan, the capital city of China’s Hubei province.

At first, there was a sense of uncertainty about the virus, but as the world continued to watch the rising cases and deaths in China and, later, other parts of the world, people started panicking over the novel coronavirus. Individuals rushed to use face masks, hand sanitizers, and social distancing.

By the end of that month, countries had airlifted their citizens out of China, and governments around the world had taken drastic measures to protect their people, including travel bans and lockdowns.

To combat the virus, Ugandan President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni imposed a total lockdown on March 25, 2020, restricting the movement of public and private vehicles, among other things.

By April 2020, the whole world was in total lockdown. Mandatory wearing of face masks, remote working, and distance learning became the new normal. With close to zero movements allowed, Zoom calls eventually replaced physical meetings as a way for people to keep in touch with each other. This stifled the economy, with businesses closing and many people losing their jobs.

For many, 2020 was marked as the ‘worst’ year in the 21st century. Three years later, with over six million lives lost, children orphaned, and hundreds laid off from work, the COVID-19 pandemic and its resultant preventive measures are still hitting hard. One of the impacts COVID-19 has left is the post-covid syndrome,” which entails a variety of ongoing symptoms that people experience after suffering from COVID-19.

In 2021, Joseph Mukaawa lost his father to COVID-19. When he came back from the burial, he started developing signs of COVID-19 and tested positive. “I thought that since I was young, I could overcome it. So, I started self-medicating,” he said.

But three days later, the fever was not going down. He went to a nearby clinic where he would be treated. When he woke up the following morning, he felt himself losing oxygen. “I could not understand what was going on. All I recall was asking to be rushed to another medical center,” he said.

For the 12 days he spent there, he was on oxygen and unconscious from time to time. A few weeks into his recovery, he had erectile dysfunction for over a month. He was advised not to do heavy exercises since his lungs had not fully recovered.

Close to two years later, he still feels the impact of the disease. “My body got weak. I still lose oxygen when I try to do heavy work. I don’t know how long I will spend in the world because I took experimental medicine,” Mukaawa said.

Besides that, he also suffers from occasional memory loss, and however much it has not directly affected his work productivity, Mukaawa is not able to remember certain details, especially names and messages he has to deliver.

Even as he was completing his Master’s degree last year, he was still facing the same issue. “I thank God we were doing online exams because if I were to do sit-in exams, perhaps I would not pass,” he said.

As much as it is subsiding now, Mukaawa is not who he was before he got COVID-19. He still goes for checkups every six months to ensure that his organs are recovering.

Mukaawa is not the only one. Many survivors have continued to deal with complications even after recovery. Maureen Wabuna, a student at Uganda Christian University (UCU) pursuing a Bachelor of Business Administration, says she has become forgetful since her recovery and has a low concentration span.

“I tend to forget a lot, and I cannot focus in class for long like I used to. I get to a point where I cannot understand what is going on,” Wabuna said.

Esther Aguko, the UCU Vice Chancellor’s Executive Officer, said her sleeping pattern has changed ever since her recovery. “I sleep less now, and my concentration span is too low. Probably, there are other people facing similar issues, but they are not aware,” she said.

At least 65 million individuals worldwide are estimated to have long-term COVID, with cases increasing daily. According to the findings of a long-term study, 85% of patients who had symptoms two months after the initial infection reported symptoms one year later.

A study by Stephen Phillips and Michelle A. Williams describes this post-covid syndrome as the next public health disaster in the making. There is an urgent need for empirical data indicating the scale and scope of the problem to support the development of an adequate healthcare response.

Brian Mathina, a doctor at Rubaga Hospital in Kampala, says post-covid syndrome is mainly common in people who were not vaccinated and had severe COVID-19. In every 10 people that suffered from COVID-19, about 2–3 people present post-COVID symptoms. These may be symptoms that the patient previously had or even more newly added symptoms.

“Some people present with difficulty breathing, chest pain, coughing, and at times allergic reactions in some people,” he said.

In certain cases, COVID-19 survivors develop fibrosis. This is the scarring within the lungs where the normally thin, lacy walls of the air sacs become thick, stiff, and scarred, making them less efficient at delivering oxygen to the bloodstream. This means that there is more effort to breathe, thus leading to shortness of breath in some cases.

When asked about what the cause of memory loss in some of the survivors could be, Mathina said it has not yet been scientifically proven as a post-covid effect.

However, he says, “We cannot say it does not exist because that is something that has been seen in some people who have come for post-covidien care. We are yet to find out if COVID-19 affects the Broca’s area in the brain,” he said. Broca’s area, also known as the motor area, controls breathing patterns and vocalizations required for normal speech.

Mathina says people should seek medical help when they present with post-covid symptoms. “A doctor will evaluate you and find ways of helping you. He will also be able to know if the effect is from COVID-19 or other illnesses,” he said.

He recommends that people take mental state exams to determine whether they have memory loss. This examination is a structured way of observing and describing a patient’s current state of mind under the domains of appearance, attitude, behavior, mood, speech, thought process, thought content, perception, cognition, insight, and judgment.

“The doctor will determine what kind of memory loss it is and how the patient can be helped,” Mathina said.

He encourages people to go for regular screening for other illnesses and also have a good body weight. He adds that people should boost their immunity. “Avoid smoking, reduce your alcohol intake, eat citrus fruits, and drink at least 2.5 liters of fluids every day,” he said.