By Ainembabazi Gertrude

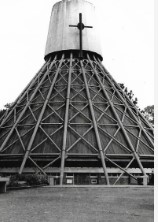

As millions of pilgrims make the long, dusty walk to Namugongo every June 3rd to honour the 45 Uganda Martyrs, the story told from pulpits and history books is strikingly familiar: young male Christian pages, burnt and speared for their faith between 1885 and 1887 under the rule of Kabaka Mwanga II.

But buried beneath this heroic narrative is another story, one that has remained largely invisible for more than a century. Fresh research by Rev. Dr Olivia Nasaka Banja, a theologian and former lecturer at Uganda Christian University (UCU), has brought to light the forgotten women whose courage and faith shaped the early church but never made it into mainstream history.

Her study, “Women and the Uganda Martyrs. A Forgotten Chapter” paints a fuller picture of the martyrdom story by revealing the mothers, widows, princesses, and evangelists who stood behind the famous boy-pages.

“Every martyr was born of a woman, breastfed by a woman, and raised by a woman,” Rev. Banja writes.

While the kingdom’s young converts were led to execution, their mothers prayed, mourned, and sustained the early Christian movement under intense persecution. Their resilience, she argues, formed the spiritual backbone of Uganda’s first Christian community.

One of the earliest women restored to the narrative is Sarah Nakima, also known as Sarah Nalwanga. Arrested in 1885 at Busega alongside the young martyrs Makko Kakumba, Noah Sserwanga, and Yusuf Lugalama, she refused to escape even while holding her nursing infant.

Customs against killing a mother with a suckling child saved her life, but she was forced to watch the boys burnt alive. She was later tortured for her faith.

Despite her central role, Sarah’s name rarely appears in the story told at Namugongo.

Another woman Rev. Banja spotlights is Mubulire Fanny, widow of martyr Fred Kizza. Instead of collapsing under grief after her husband’s death at Namugongo, she took up his torch—teaching palace servants and evangelising in her community.

“The fire that burnt her husband left a scar on her heart,” Banja writes, “but it also ignited the flame of faith.”

Her story is one of many examples showing how women sustained the church long after the executions ended.

Perhaps the most dramatic story is that of Princess Clara Nalumansi, sister to Kabaka Mwanga II. In a royal household where Christianity was considered treason, Nalumansi secretly converted, destroyed her shrines, and married in church.

She once warned missionaries Alexander Mackay and R.P. Ashe of Mwanga’s plans to kill them an act of defiance that saved their lives.

But her faith eventually cost her own life. In 1889, King Kalema, who briefly usurped the throne, ordered her burnt to death for her growing influence among Christian converts.

“She was the princess who chose Christ over the crown,” Rev. Banja notes.

The research also highlights Lakeeri (Rachel) Tebulimbwa Ssebuliba, a widow and gospel teacher who volunteered to evangelise in the sleeping sickness–ravaged Buvuma Islands around 1900.

Warned by Bishop Alfred Tucker that the mission meant almost certain death, she insisted on going.

“I go,” she said, “for many have not yet heard of Christ.”

She later died of the disease but converted many before her passing. Lakeeri’s legacy lived on—her grandson, Dunstan Nsubuga, would later become Bishop of Namirembe Diocese.

Rev. Banja situates these women within the period when Christianity took root in Uganda. While men faced fiery martyrdom, women kept the faith alive through teaching, baptism, prayer, and community-building.

“They were the backbone of the church,” she writes. “Yet history treats them as footnotes.”

The research also connects historical injustices to modern realities. Today, women make up nearly 80 percent of church congregations but hold only 5 per cent of leadership roles. They contribute most of Uganda’s agricultural labour yet own a fraction of the land. Fourteen women die every day from maternal causes.

“These realities”, Rev. Banja argues, “betray the legacy of the martyrs.”

As pilgrims kneel at Namugongo this year, Rev. Banja urges Ugandans to remember the full story, one that includes:

“The Church in Uganda was born from the womb of women,” she writes. “To tell the martyrs’ story without the women is to tell half the Gospel.”

More than 139 years later, the fire of Namugongo still burns—not only in honour of the young men who died, but also in memory of the women whose silent courage kept the faith alive.