By Esther Nantambi

In 2017, as I awaited my undergraduate graduation, I joined the Youth Equality Center Radio, an online advocacy station where I hosted the show “Make Power.” The show focused on promoting gender equality. It was through this show that I got my first opportunity to get onto a plane and meet many young advocates globally. Despite my advocacy work, I had always been hesitant to associate with the term “feminist.” I believed, and still do, that the discussion on feminism has extremes that disrupt the complementary balance between men and women in society.

My standard point was challenged in my African Christian Theology class at Uganda Christian University, which introduced me to an article in the Journal of Anglican Studies published by Cambridge University Press and written by Rev. Canon. Prof. Christopher Byaruhanga in 2010. It is titled “Called by God but Ordained by Men: The Work and Ministry of Reverend Florence Spetume Njangali in the Church of the Province of Uganda”. The piece is a powerful testimony of the excruciating journey toward ordination for the first woman to be admitted into theology school.

This story is a captivating narrative of true events, scoring highly on Byaruhanga’s use of primary sources including Njangali’s relatives, contemporaries and herself. Byaruhanga gives details of different stages of Njangali’s pursuit of ordination, from inception to its attainment and thereafter.

So, did ordination bring about a happily ever after?

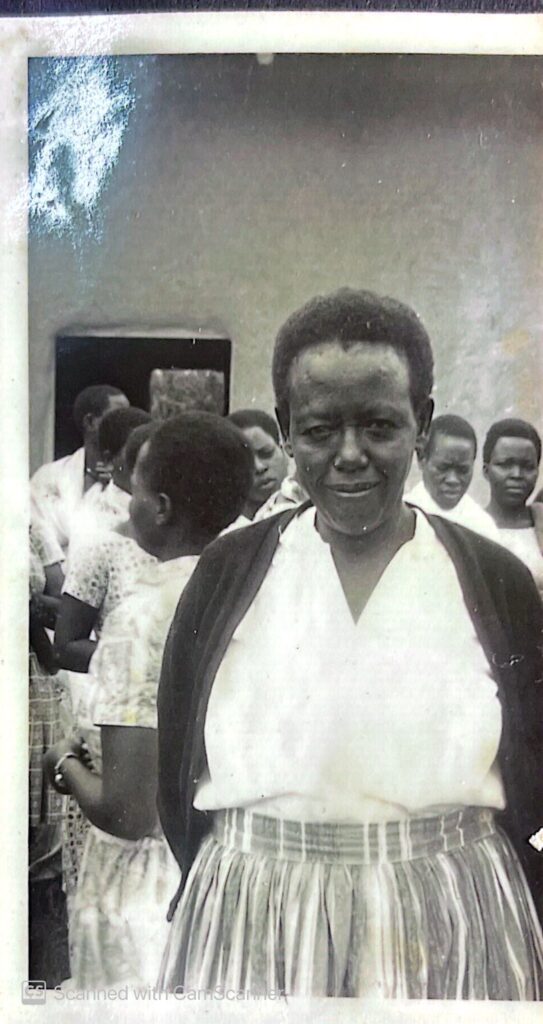

Byaruhanga’s piece tells us that Njangali’s story begins in Hoima, western Uganda, where she was born in 1908 to a devout Anglican Christian family. Njangali’s uncle, King Bisereko Duhaga II, and her education under devout Christian instructors laid the groundwork for her spiritual and professional calling. She pursued teaching and first became the headteacher of Duhaga Girls’ Boarding School, before making a turn to join Bishop Tucker School of Divinity and Theology (BTSDT) for a lay reader course in the 1950s, leaving behind her lucrative job. Njangali’s admittance to BTSDT sent shock waves throughout the nation. “How could a woman be admitted into the divine ministry?” many wondered. Their shock was telling. At Bishop Tucker, Njangali would soon learn that being admitted and being accepted by colleagues and relatives were two different things.

Her initial challenge was discovering that there was no place for her in the lecture rooms. Byaruhanga quotes Njangali, “I was told to sit outside and study from the veranda!” In addition to this humiliation, her male counterparts doubted her capacity to absorb the complex content of theology. But she did not walk away, instead, she made it a point to participate in the discussions in class.

Her saving grace was her academic prowess and spiritual depth which earned her respect among her peers and mentors.

Upon completing her studies in 1960, Njangali’s male counterparts were routinely ordained and integrated into the church’s leadership, while she was posted as a “church commissioned worker” to head the Mother’s Union in Ankole-Kigezi Diocese. As she served, Njangali advocated for equality, envisioning a church where men and women participated according to their gifts. She found allies in progressive clergymen but also encountered staunch opposition from traditionalists.

Byaruhanga points out that despite the challenges, Njangali sought to remain steadfast on scripture, often advocating not for one sex over another but for biblical principles to reign. “Njangali warned women deacons and other women church workers against the attitude of competition between them and men, a power struggle and a search for positions of dominance, or mere wars between the sexes. Njangali’s argument was that no matter how logical an argument in support of ordination of women might seem, if it deviates from the biblical values of equality, mutual respect and the dignity of persons, that argument ceases to be valid,” Byaruhanga writes.

She argued that Bible texts must be approached neither from the point of view of women nor from the point of view of men.

Following the Lambeth Conference of 1968 which agreed on women deacons and the subsequent, Anglican Consultative Council meeting in Limuru, Kenya in 1971, which supported priesting women, Njangali was ordained as the first female deacon in East Africa on September 10, 1973. This outraged a number of lay people and priests who believed it not biblical to ordain a woman. Although she was never fully priested, her ordination broke the ecclesiastical glass ceiling, paving the way for future generations of women in ministry, and in 1983, Bishop Festo Kivengere of Kigezi ordained three women as priests. The church has continued to ordain female priests since.

Reflection on gender equality

Reverend Njangali’s story resonated deeply with me. Byaruhanga tactically uses her story to demonstrate that the struggle for gender equality within the church is not about extreme ideologies but about ensuring that women can fulfill their callings without unjust barriers.

My classmates usually comment that I love to raise my hand, yet now, I painstakingly realise that for me to simply sit on a chair next to a man and raise my hand, a price had to be paid.

Angelou Maya’s once made a statement:“Each time a woman stands up for herself, without knowing it possibly, without claiming it, she stands for all women.” This is what Nganjali did when she accepted her call and joined an all-male institution. She paved the way for many of us.

From one student in 1954 when Njangali joined, today, BTSDT has 50 female students pursuing an ongoing education, according to the registrar for the school, Jean Asasira. This is a number excluding students in seminaries elsewhere.

In addition to this, the estimated number of active female clergy is 300, according to data from the Provincial Clergy Women Association.

The progress has been slow, considering that it has been 70 years since Njangali’s admission in BTSDT and 51 years since her ordination as deacon, but it is substantial.

Women in the Province of the Church of Uganda still wait to attain certain positions in the ecclesiastical ceiling, yet Njangali’s legacy reminds us of the importance of small strides that eventually snowball into big movements. Her journey highlights that patience, perseverance, faith, and resilience can overcome even the most entrenched barriers.

It also shows that all we female ministers have a debt to pay. As a person enjoying the benefits of a sacrifice, what ground are you leveling for those who shall come after you?